Information Metabolism

Metabolism of Information

Basic Notion

The model of information metabolism was first presented by Kępiński (1970) and then further developed by him and others. Kępiński claimed that technical models impose a dualistic characterization of human beings—thus implying that mental processes govern somatic processes mechanistically and explaining very little about psychological life, e.g., experiences, creativity. He considered biological models to be closer to psychological reality than technical ones, because they take life into consideration.

The term “energetic-informational metabolism” was used by Kępiński (1970, 1979a) to denote life, or more specifically, two processes without which life would not be possible. In the initial phases of phylogenetic development, energy metabolism dominates, but it always coexists with information metabolism, e.g., processing of information concerning sources of nourishment. As development progresses, information metabolism gains greater importance and, in extreme situations, all available energy is utilized for information processing. The information-metabolism model is based on an analogy with the structural organization of the cell, and attempts to describe information processing as analogous to energy metabolism. According to Kępiński (1970) the “metabolism of information” (i.e., processing of information) functions like a cell, i.e., it has its own border, analogous to the cell membrane; a control center similar to the cellular nucleus; a system for information distribution and processing, similar to the endoplasmic reticulum and lysosome; and a source of energy, similar to the mitochondria. At the basis of the theory lies a need for information input which varies with time, as is acknowledged by other theories of information processing. Kępiński’s view was based on a generalization of Carnot’s principle, which states that “the organism is an open system and its negentropy rises or falls as results of processes described by the laws of life conservation and species conservation, respectively” (Struzik, 1987a, p. 107). These are two principal biological laws recognized by Kępiński. He also describes two phases of such metabolism. The first phase, which is almost entirely involuntary and localized in lower parts of the brain (diencephalon and rhinencephalon), establishes a basic attitude “toward” or “against” some aspects of the environment. The second phase, which is voluntary and localized in the neocortex, is responsible for active behavior in relation to the environment.

Basic Functions and Structures

Control Center

Information metabolism occurs within a defined space and time. It has a control center (CC)—i.e., ego or the “I”—and functional structures enabling reception, processing, and assimilation of information, as well as regulation of the organisms‘s own activities. Information metabolism is determined by the phylogenetic and ontogenetic past of organism, but it is also involved in pursuing aims which extend into the future. It creates individually varying pictures (i.e., functional structures) of the outside world, which although objectively uniform are perceived as unique and different by each individual.

Functional Structures

The term “functional structure” is used by Kępiński for schematic representation of perception and activity.

System of Values

Decision-making is recognized as one of the basic features of life; it has different degrees of freedom in different organisms—limited in the most primitive organisms and a maximum value in humans. The hierarchy of values governs the mechanisms selecting and filtering the information reaching any particular decision-making level. This system of values has three levels (Kępiński, 1977b):

- The first one is biological and is concerned with all that is described by the concept of biological programming (i.e., all that man is born with and can control to some extent). It is determined by two basic biological laws: self and species preservation. Depending on how well they are established one can speak of greater or lesser life dynamics of an individual.

- The second level determines an emotional attitude (i.e., “towards” or “against”). It is characterized by the formation of complexes, which are emotional centers where an individual’s emotional relations meet with the environment. These centers are usually formed around an important person from childhood and influence a person’s emotional relationships in later life. Complexes can also arise in connection with traumatic situations and can shape an individual’s attitudes toward similar situations that occur later in life. Complexes become fixed by repetition. The biological and emotional levels are located below the threshold of consciousness, meaning they are automatic. They shape a “real hierarchy of values” (“I am really like this”) based on fixed and automatic tendencies, habits, and attitudes.

- The third level is sociocultural and determines how an individual projects himself into the future (“I would like to be like this, these are my goals, this seems most important to me”). This level is conscious and consists of an individual’s aspirations, ideals, and cultural models. It refers to the hierarchy of values of one’s social environment.

The real hierarchy of values is more important in the process of decision-making, but final decisions are determined by all levels of the system of values, including the ideal hierarchy. Therefore, an individual’s will can control his or her behavior to a certain degree.

Maintaining Order

“Order is the essence of the structure. The preservation of structure and order in the metabolism of energy requires no effort, at least no conscious effort, for this is taken care of by physiological mechanisms. Their preservation in information metabolism is connected with continuous efforts focusing on the proper selection of information coming from the outside and inside of the organism and on the choice of proper forms of reactions. This integrational effort is largely unconscious. However, the part that reaches our consciousness is enough to realize how much effort it requires to keep order in the chaos of contradictory emotions, ideas, plans and ways of looking at the world and ourselves, etc. Integrational efforts are conscious when they take shape in an act of will. Information metabolism is subjectively experienced as a pressure of sensation coming from the world outside, which man tries to arrange and sort out under greater or lesser tension and due to which the world of man’s experiences constantly changes its theme and color” (Kępiński, 1979a, p. 191), and from the world inside, which is made up of signals coming from the interoreceptors and man’s own mental activities: dreams, plans, memories, fantasies, thoughts, and the like.

Autonomic Psychological Activity

Daydreaming is the best example of man’s own mental activities. “Daydreaming is something which is most ‘mine’—one has an absolute power over it, while having no power over reality. One can only fight for it, winning or losing in turns. The weaker the possibility of expansion and the greater the number of limitations to one’s own sphere of existence, the richer and less realistic dreams become. In the conscious state, however, there are some limits of tolerance to own’s fantasies.” When “fantasy becomes too fantastic, i.e., when it no longer can fit in the structure of the real world, it becomes something strange and surprising, dangerous, and comical. The world of daydreams is reduced under the pressure of reality; what is unreal is pushed to the margin or totally disappears from consciousness… however, that which does not fit the structure of the real world occurs in dream visions at night. Daydreaming (…) belongs to the same sphere of experiences as thinking, planning and dream visions in sleep. The limiting influence of the structure of the real world is much stronger in the first two phenomena and much weaker in the third. This freedom is much greater in daydreaming. One is sovereign ruler over one’s world of dreams. In the case of sleep the situation is reversed. It is true that present reality has hardly any influence on the form and content of one’s visions, but, at the same time, one has no power over them. On the contrary, one remains in the power of one’s visions, from which it is only sometimes possible to free oneself by waking up an a strong act of will” (Kępiński, 1979b, pp. 178–181).

Sense of Reality and Feedback between an Organism and Environment

One of the rules governing information metabolism says that the world around is changeable and the organism is stable (Kępiński, 1979a). Any change in the structure of the exchange of signals with the environment provokes an orientation reflex, which is accompanied by the feeling of anxiety. The force of the vegetative and emotional reaction to the outside stimulus depends on the force and the unusualness of the stimulus and on the present state of consciousness. The reaction is exceptionally strong when the signaling system is in a state of low selecting ability (e.g., in sleep), which can be shown as a scale of values changing with the situation and making one set of signals reach the organism more easily than another.

The degree of total integration of the functions of man’s nervous system is proportional to the state of consciousness, e.g., aware responsiveness to the environment. Any break of contact with the surrounding world causes a relaxation of this integrating process. The sense of reality is directly dependent on man’s sensorial contact with the environment. In man’s sense of reality there is a lot of habit and belief. Its order is disturbed whenever man faces a new, unusual situation, when he experiences an accumulation of too many positive or negative emotions, or when, for a longer period of time, his actions are influenced by his negative emotional attitude toward the world around him and to himself. The monotony of such an emotional state makes life dull, unpleasant, and boring so that its reality becomes blurred. In sleep reality is made up of dream visions, while in a conscious state it is made up of the world around. Doubts arise when we consider the border between sleep and wakefulness. In the state of wakefulness man is in a strong feedback relationship with his surroundings; the perception threshold for exteroceptive stimuli is lower and for interoceptive stimuli it is higher. In sleep, on the other hand, the feedback relationship with the surroundings is diminished. We can consider the rhythmicity of sleep and wakefulness as a changing reactivity to exteroceptive and interoceptive stimuli, changing man’s relationship with the environment.

A Model of Information Metabolism

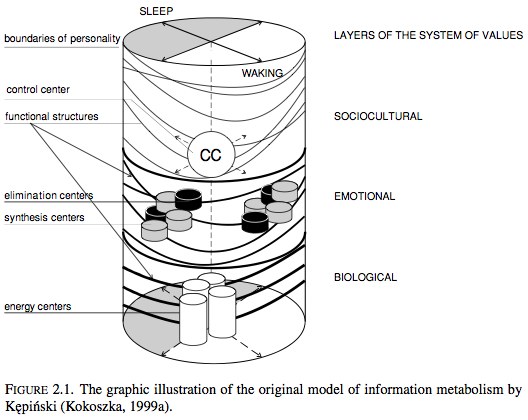

The metaphor of information metabolism expresses the thesis that human experience and behavior cannot be explained by a technical model of information processing. This process in humans is influenced to a significant degree by the subjective meaning of information, which was shaped during the person’s individual life-history. The unique set of experiences contained in the functional structures of a system of values includes, especially at the emotional level, subjective emotional complexes. These complexes cause human behavior in some situations to be directed by subjective feelings, rather than objective logic. For this reason the notion of information metabolism in human seems to be more adequate than that of information processing. The model applied by Kępiński of information metabolism, in its essence, enables us to differentiate the main elements in the structure of human experiences, analogous to the structure and functions of biological cell. These are presented in Figure 2.1:

- Central Point—“I,” or control center (“CC” in the figure). This structure corresponds to a universal experience of being a subject of one’s own psychical activity, which controls overall one’s own activity, like the nucleus, which governs the biological cell activity.

- Boundaries (the whole cylinder in the figure), considered in the sense of self-identity, as a means for enabling discrimination of one’s own limits and differentiating oneself from other people and from the external world.

- Functional structures shaped in earlier life, which maintain order in space and time and layers of systems of values. Creation of this structure may be compared to synthesis of biochemical compounds of a biological cell.

- Centers of energy necessary for preservation of metabolism or information, i.e., proper stimuli reception, selection and integration, as well as decision-making.

- Centers of elimination, where useless and unimportant information is removed.